Garlic – The Great Traveler

The history of garlic can almost be described as the history of human migration. Garlic is native to Central Asia, specifically the Caucasus region between the Black and the Caspian Seas, and over many millennia it has been carried to almost all corners of the world. Garlic flavours many of the world’s cuisines. It is steeped in folk lore and legend. (Everyone knows that wearing garlic is the best way to keep vampires at bay!) Folk wisdom attributes garlic with a variety of curative properties, many of which have been proven by contemporary science. Garlic is mentioned in ancient Egyptian, Greek, Indian, and Chinese writings as well as the Bible and Koran.

The history of garlic can almost be described as the history of human migration. Garlic is native to Central Asia, specifically the Caucasus region between the Black and the Caspian Seas, and over many millennia it has been carried to almost all corners of the world. Garlic flavours many of the world’s cuisines. It is steeped in folk lore and legend. (Everyone knows that wearing garlic is the best way to keep vampires at bay!) Folk wisdom attributes garlic with a variety of curative properties, many of which have been proven by contemporary science. Garlic is mentioned in ancient Egyptian, Greek, Indian, and Chinese writings as well as the Bible and Koran.

Garlic was first brought to North America by immigrants from Poland, Germany and Italy, but most of the varieties we use now came into the US in 1989. In the 1980’s the USDA tried to get permission to collect new garlics in the Caucasus region, then part of the Soviet Union, but were denied because of military installations in the area.

Red Russian garlic

In 1989 the Americans were finally granted permission to enter the region, but were heavily guarded and allowed to travel only at night. They travelled along the old Silk Road and purchased garlics from local markets, often naming them for the towns and villages they were found in. (Red Russian garlic, one of our most popular varieties, was actually brought into BC by the Dukhobors in the early 1900’s and is now considered to be a BC heritage variety.)

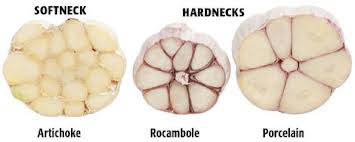

Garlic, or Allium sativum, comes in two basic types – hardneck and softneck. Hardneck varieties (var. ophioscorodon) usually grow a woody flower stalk or scape out of the centre of the bulb. They do best in cold, damp climates. Typically a bulb develops four to ten large cloves. Flavours are strong and often spicy and complex. Most hardneck garlic does not store well and is best used fresh. Hardneck varieties come in three different types: Rocamboles, which have thin parchment-like skins, and are easy to peel, Porcelains which have thick tough skin and do store well, and Purple Striped, named for their distinctive colouring.

Softneck garlic (var, sativum) evolved from hard-neck varieties and grows best in warmer climates. Bulbs keep well and typically contain multiple cloves. They don’t produce flower stalks unless they are stressed. Softneck varieties come in two different types: Silverskin and Artichoke. Silverskins have soft pliable necks that lend themselves to braiding, lots of small cloves and spicy flavours. Artichoke garlic has larger but fewer cloves and a milder flavour. Most of the commercially grown garlics found in the grocery store are soft neck varieties.

Elephant garlic (Allium ampeloprasum) is actually more closely related to leeks than to garlic. It produces a small number of very large cloves of mild flavour. It needs a good, long, warm growing season to grow well.

Tips for Growing Good Garlic

Choose an open, sunny site with light, well-drained soil. Incorporate lots of organic matter, such as well rotted manure or good compost into the soil. Garlic won’t thrive in acid soils (below 5.5pH) so be sure to apply lime if your soil is acidic.

Plant garlic in October so it can develop good roots before the winter.

Separate the cloves

Break up the bulb carefully into individual segments prior to planting. Try to leave the skins intact.

Make sure that the cloves are planted the right way up: the flatter basal plate should be facing downwards

Allow about 4” between individual cloves and 1 foot between rows. Plant the cloves so the tips are one inch below the soil surface.

If your soil is heavy and wet you could start your garlic off in small pots, or divided trays in the fall, overwinter them in a cold frame and plant them out in the spring.

Mulched garlic

Over the growing season hand weed regularly. Hoeing can be tricky as the bulbs are so close to the surface. Mulching, with shredded leaves or straw, will help with weed suppression.

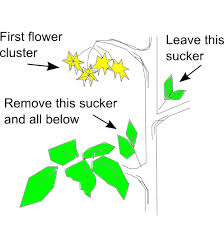

Hardneck garlic cultivars readily produce flower stalks which should be cut off as soon as they appear. They are delicious in stir fries!

Garlic scapes

Garlic matures between the end of July and early August. Stop watering a few weeks before harvesting to allow the bulbs to cure. Harvest when 1/2-3/4 of the leaves have turned yellow (depending on variety). Don’t delay as the bulbs open up and won’t store as well if lifted late.

Lift the bulbs with a fork. Handle gently as bruising also reduces their storage potential.

Dry the bulbs thoroughly, spread out in a single layer in the sun or in a dry, well-ventilated shed or similar environment. Drying will take two to four weeks depending on the weather. When the foliage is dry cut off the stalks and store the bulbs in a cool dry place. Do not store in the refrigerator. This will induce sprouting, changing the garlic’s texture and flavour.

It’s interesting how idle thoughts, in this case, “I wonder why the names of garlic cultivars are so exotic”, can lead to a voyage of discovery. The story of garlic is fascinating, and I’ve barely scratched the surface here. If you’d like to learn more, these websites are particularly informative:

http://www.gourmetgarlicgardens.com/overview.htm

Copy this URL to look at an in-depth report on garlic growing in BC put out by the Ministry of Agriculture:

https://www.al.gov.bc.ca/speccrop/publications/documents/garlic.pdf