By Brian Russell

Established woody plants (trees, shrubs and conifers) are best moved when they are fully dormant. In our climate, this means November, December, January or early February. In theory you can move just about anything if you have enough determination and manpower (or womanpower!)

The tree in these photos is an Acer palmatum ‘Shishigashira’ that has been in our roadside planting for almost 25 years. It has long been too big for the space and rather than cut it down we decided to try to move it. It was a big job that required several people, a tractor and a sturdy trailer. Hopefully it will survive the move and settle in to its new home in the garden of one of our staff.

The spade must be sharp to cut the roots

It’s important, and a lot easier, to use a sharp shovel or spade because you need to sever the roots cleanly. A dull edge will leave a lot of damaged, torn roots, making it much harder for the plant to re-root. Use a coarse flat file to hone a nice sharp edge on your spade. If you have access to a bench grinder, all the better. If you are planning to do a lot of transplanting, you might want to keep one nice, sharp, clean garden spade just for transplanting. The ones with a square edge and a short sturdy handle with a “D” shaped grip are best.

Starting to severe the roots

Before you start digging, tie up the branches to get them out of the way and to protect them from breakage. You can use rope or twine as long as it is reasonably soft and won’t damage the bark. Almost any large shrub or small tree will be easier to dig and maneuver into its new home if the branches are wrapped.

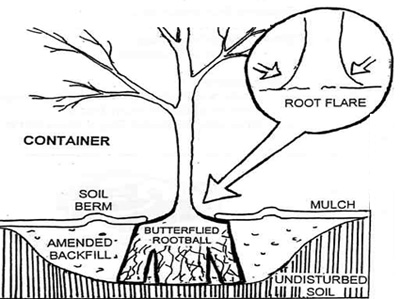

Clear away all the leaves and debris around the base of the plant and then start slicing your way through the roots, angling inwards as much as downwards. You should be digging at an angle so that you will end up with a cone-shaped root ball. The rule of thumb for determining the size of the root ball to dig is as follows: allow ten to twelve inches of root ball diameter for every one inch of trunk calliper.

Close up of root severing

For small plants, you might be able to dig a nice root ball out with just six or eight “slices” of your razor sharp shovel blade. For larger plants, you will need a larger root ball but the shovel’s blade won’t be long enough to get all the way under the plant the first time around.

Tipping the tree to cut the final roots

First, dig a full shovel depth all the way around the plant and then get a helper to use another shovel as a lever to lift, very slightly, the partially severed root ball so that you can get in and slice the remaining roots. At this point it’s not usually possible to use your foot on the shovel anymore because it’s so deep in the soil. Just push it in by hand and slice through the rest of the roots until the plant is ready to lift.

Protect the root ball by lifting it carefully onto a tarp and dragging the tarp to the plant’s new home. Ideally it should be replanted as soon as possible to minimize transplant shock. If you can’t plant it right away then you should wrap up the root ball entirely with burlap (or an old towel or part of a bed sheet) and secure it tightly with twine. Treated like this, it can be heeled into a holding bed and kept there for weeks or even months before it is planted out again.

Ready to transport

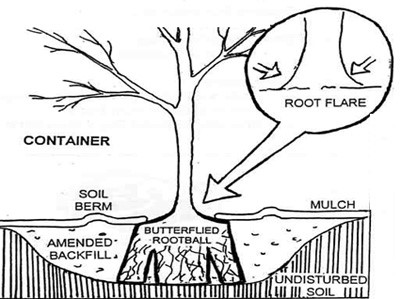

When replanting, ensure that you are planting at exactly the same depth: no higher or lower than the original location. Add bonemeal to the back fill soil to stimulate new root growth, water in well to dislodge air pockets, untie the poor thing and prune off the broken branches (there will surely be some).

The tree all ready for the journey to its new home!

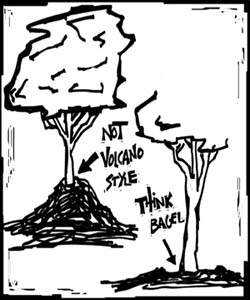

A significant portion of that plant’s roots stayed at its former location, and the roots that remain will need to receive more moisture than usual, with mid to late summer being the most critical time. You won’t really know if the plant has survived the transplant process for at least a full year. Treat it like a new planting and pamper it a bit more than usual. Mulching will help, and so will building a little soil ‘donut’ or basin around the plant where you can put your hose on “trickle” three times a week.